“No sane person fears nothingness.”

– Tibetan Book of The Dead

The drive from Pangong Tso to Tso Moriri was a journey through nothingness. Clearly demarcated paths did not exist for a large part of the route and all we did was trust the instincts of Dorje Saheb and rode through dirt tracks that went straight through a barren land surrounded by high mountains on both sides. It was eerily quiet out there, not a soul in sight except two vehicles that had set out from Spangmik in the morning. Not even the omnipresent military was in sight for a long time and we were on our own; difficult to believe that we fought a war for a land where no body actually lives. In the absence of any human presence outside, we transcended the sense of space and time, something that is so beautiful about Ladakh. It could have been any century and the view ahead would have looked almost the same. The road to Tso Moriri, though not oft taken, is as charming as the destination itself.

A Road Less Taken

Most tourists going to Pangong Tso return to Leh even if they have to go to Tso Moriri. A dirt track along the lake can take one towards Chushul and beyond. The road is non-existent for a better duration of the journey, loose soil and sharp rocks are commonplace, and one may even get stuck in quicksand on a (un)lucky day. However, this desolate and difficult route is also one of the most beautiful in Ladakh and takes one through breath-taking landscapes and places of great interest. We decided that it was this way that we would roll.

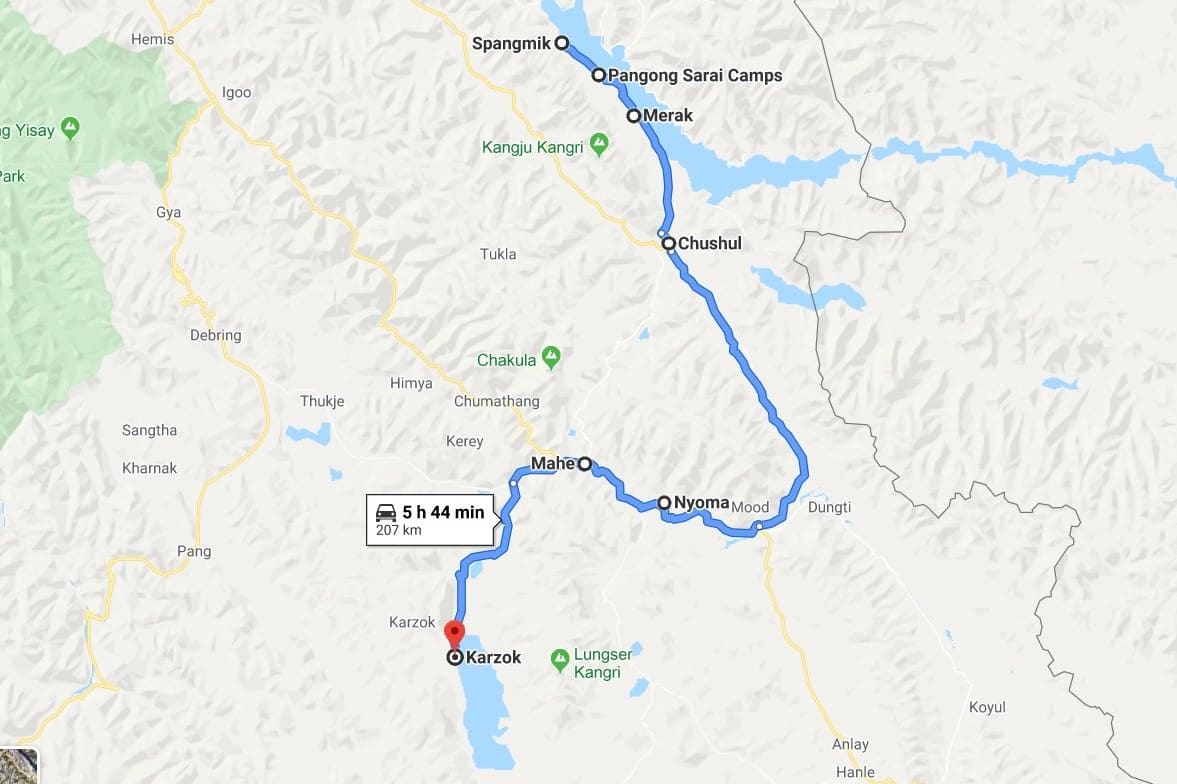

Our journey took around 8-9 hours and passed through Spangmik > Man > Merak > Chusul > Tsaga La > Loma Bridge > Mood > Nyoma > Mahe Bridge > Sumdo > Karzok.

A Drive Along The Pangong Tso

So on a very cold morning, we were packed again and were already on our way to Tso Moriri. Our only companion through the journey was another tourist vehicle, the driver was apparently new and this was his first trip on this route. Dorje saheb very generously decided to act as a guide for everyone, on the condition that he would keep behind our vehicle.

For about 20 KM, we drove along with the Pangong Tso, its blue waters glittering in the morning sun and grey-brown mountains on the background. We crossed Merak, a small hamlet which is also a military check-post, and turned right bidding adieu to the lake at the point where it turns into the Chinese occupied territory. Behind the brown mountains was a taller mountain darker in colour, almost black. The brown mountain was Indian while the Chinese sat on the black mountain. Between the two somewhere runs the vaguely demarcated Line of Actual Control (LAC). Though we could not see the Chinese positions from our locations, it was goosebumps worthy nonetheless.

A drive on this route redefines isolation for you. There is no phone signal, no petrol pumps, mechanics, shops, people, not even a road. You are on your own with, and against, the elements. The only thing that lies between you and death is a working engine, tyres with air in those, and a reliable driver. It did not occur to us then, but it is not difficult to understand why this road is so less travelled.

On The Roof Of The World In The Changthang Plateau

Located at an average altitude of 14600 ft above sea level, the Changthang plateau stretches from Eastern Ladakh to the interiors of Tibet almost 1600 km away. This land is home to the Changpa people, semi-nomads of the Tibetan stock, who have wandered in the inhospitable terrains of this plateau for centuries. They rear yaks, sheep, and goats which produce fine quality wool including the Pashmina.

The landscape of Changthang is as moody as its weather. We walked in the shadows of tall mountains, between gorges and sometimes on terrains as flat as the Rann of Kutch. The dramatic vistas unfold in front of the visitor like the acts of a Shakespearean play, one breath-taking scene after another and the camera just does not stop clicking.

Settlements are few and far in between. Apart from some flat-roofed houses in the scanty villages that come on the way, one can see white tents of the herdsmen erected in the areas with access to grass and water. The hutments usually have a circular stone enclosure adjoining them, meant to keep the animals safe from the elements and predators. As informed by Dorje saheb, the Changpas are predominantly Buddhists and follow the Tibetan school of Buddhism. There have been winds of modernization in their centuries-old lifestyle and the effects are yet to be ascertained.

At first glance, it is difficult to imagine that the seemingly barren earth of Changthang will support any wildlife. However, that is not the case. The plateau is home to a number of avian and animal species from the wild, including Kiangs (Ladakhi Wild Ass), Black Necked Cranes, Tibetan Wolf, Wild Yak, Tibetan Gazelle, Antelopes, Lynx and the enigmatic Snow leopard. While driving through the area known as Changthang Wildlife Sanctuary, we came across herds of Kiangs (in the photo) sprinting in the rocky plains.

A Chequerboard Of War Memorials

The region around Chushul is dotted with War memorials, a reminder of the pitched battles that were fought here in the Indo-Chinese War of 1962. Chinese-occupied Ladakh is not far from here and as we drove on, we came across one memorial after another, solemn structures in the memory of the fallen soldiers who died defending this land in the war. There were memorials dedicated to 1/8 Gurkhas, 5 Jats, 1 J&K Militia, and finally, the Rezang La War Memorial of the fabled 13th Kumaon.

Ekta was not feeling well at this time, so she and Dorje Saheb stayed back in the vehicle while I decided to walk up to the memorial and pay my respect.

Rezang La War Memorial

As a kid, I was deeply influenced by a TV Serial ‘Paramveer Chakra’ that used to illustrate the stories of brave soldiers from the Indian Armed Forces who were awarded the highest battle honors of independent India, often posthumously. A few episodes were about the 1962 war and one story that stayed on with me was that of Major Shaitan Singh and how he made a last stand with his men to defend his post under overwhelming odds.

This urge to visit the place grew stronger after I watched Chetan Anand’s Haqeeqat (1964) and was reinforced from further readings to a point that through this trip I was waiting to visit Rezang La where this battle was fought. Dorje Saheb informed that the memorial will come after Chushul and we can get down there to visit the place.

The solitary memorial stands in the backdrop of the mountains, a plain structure in white and red with a large flag fluttering in the wind, a defiant reminder that this land is still ours. Ekta was still feeling unwell due to the AMS she has got in Pangong Tso and decided to stay in the vehicled as we stopped in front of the memorial, while I walked up to it to pay my tribute.

13th Kumaon and its Last Stand at Rezang La

In November of 1962, the 13th Kumaon was deployed at Mugger Hill and Rezang La in the Chushul valley of Ladakh (16,000 feet). Almost all the soldiers of this detachment were from the Ahir company of 13th Kumaon, belonging to Rewari in Haryana.

The enemy attack began on the morning of 18th Nov 1962 when waves upon waves of Chinese soldiers started attacking the Indian positions. Heavily outnumbered and without any artillery support, the Kumaonis fought a bitter battle. Under the leadership of their brave officer Major Shaitan Singh (Param Veer Chakra, Posthumous), they repulsed 7 waves of enemy attacks. When they ran out of ammunition, they engaged the enemy in fierce hand to hand combat and held the position till the last man. The Chinese could cross Rezang La after a loss of nearly 1300 of their men, and only when every man of the 13th Kumaon had made the Supreme sacrifice.

Out of 123 soldiers at the battle of Rezang La, 114 were killed and 9 were severely injured. The body of Maj Shaitan Singh was found frozen with his weapon still in his hand, a legend in the military annals of India.

As per Major General Ian Cardozo, “When Rezang La was later revisited dead jawans were found in the trenches still holding on to their weapons… every single man of this company was found dead in his trench with several bullet or splinter wounds. The 2-inch mortar man died with a bomb still in his hand. The medical orderly had a syringe and bandage in his hands when the Chinese bullet hit him… Of the thousand mortar bombs with the defenders all but seven had been fired and the rest were ready to be fired when the (mortar) section was overrun.”.

This visit to Rezang La Memorial in Chushul was like a pilgrimage. I was standing alone there, a lone tear escaped while thinking about Major Shaitan Singh and his brave soldiers. What could I offer them except gratitude? Anything else will be just mere wordplay…

Bajrang Bali Ki Jai!

(War cry of the 13th Kumaon)

The terrain became increasingly rocky and sights of human habitats rare to find as we drove on. There were ranges upon ranges of mountains, som barren, and some clad with blankets of snow. Fluffy clouds played hide and seek with the peaks, creating regions of lights and shadows as they passed over the land. I was suddenly feeling very tired and wanted to go back to sleep. Long after we had crossed the Mahe Bridge, we saw a village perched in the mountains to our right, a hint of greenery in its landscape and crops, of what I assumed barley, in its fields till we reached a fork on the road. Dorje saheb informed that the village was Sumdo and we would take a left from here to go towards Tso Moriri. That photo of the village was the last I took before falling off to sleep.

The Emerald Waters Of Kyagar Tso

“Utho Utho! Aa gaya Tso Moriri!”

I was a little drowsy due to the long trip, or maybe because of less Oxygen and had dozed off when Dorje Saheb’s call woke me up with a start. To our side laid a lake as beautiful as a dream, its pristine emerald waters shining like gems in the sun. A snowclad peak flanked the lake, completing the picture. We clumsily stumbled out of the car to look at the spectacle before our eyes, awed by its pure beauty. The lake was immensely beautiful.

There was, however, a problem; it was too small to be Tso Moriri, and there was not a soul around. Wasn’t there supposed to be a village nearby?

A laughing Dorje Saheb came from behind to tell that this was not Tso Moriri but some small lake, the name of which he had forgotten, that comes a little before our destination. Later we got to know that this dew dropped beauty in the middle of nothing is known as Kyagar Tso, a small saline water lake at an altitude of approx 4000 mt above the sea level, fed by a glacier nearby. There is a strange melancholic beauty about this lake that remains in your mind long after you have gone away. When we were returning from Tso Moriri, we stopped at the lake again and spent some time in solitude.

Karzok!

We were alert after Kyagar Tso, excited that our destination for today was approaching in no time now. In less than an hour, the dark blue waters of Tso Moriri came into view, a vast expanse of blue as far as we could see. We kept driving until we reached near the lake, the Karzok village that sits on the very banks of the Tso Moriri, deriving its soul from the lake. The village had the rustic look of what we had seen so far in Ladakh, a few houses and a lot of tents and what seemed like hotels for the tourists. We could not wait to get down and start our explorations!